You could simply look at a single genre of the man, say his symphonies, concerti or string quartets and fall under a spell, enraptured and engaged. Take his complete oeuvre of operas, songs, piano pieces with these and you could study them for years, finding endless beauty, passion, sorrow, oppression and new perspectives.

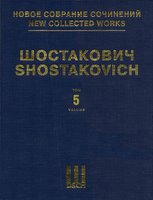

Let’s delve into two if his symphonies, Number Five and Number Ten. I highly recommend that you get a recording, a score if possible (if you read music) and listen to them yourself. These symphonies are interesting that both were premiered after he’d been denounced in 1936 and in 1948 - the Fifth was acclaimed in 1937 and the Tenth in 1953. And also that they fall in exact thirds of his symphonic output (5=1/3 of 15; 10=2/3 of 15).

So, what happens when your successful opera, Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk, gets banned (after Stalin (pictured above) saw it) and your Fourth Symphony is considered too modern? If your Dmitri Shostakovich, you comeback with an amazing, triumphal testament of sound and philosophy.

So, what happens when your successful opera, Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk, gets banned (after Stalin (pictured above) saw it) and your Fourth Symphony is considered too modern? If your Dmitri Shostakovich, you comeback with an amazing, triumphal testament of sound and philosophy. The Fifth Symphony by Shostakovich, comes from 1937, which always surprises me for some reason, I think it sounds more modern than the 1930s. It certainly struck a chord (pun INTENDED) with the Soviets, at its premiere it was well regarded (talk about a time for a standing ovation, all too common today, but for this symphony’s world premiere, I can’t think of a more deserving work!) Shostakovich himself stated: “The idea behind my [Fifth] symphony is the making of a man. I saw him, with all his experience, at the centre of the work, which is lyrical from beginning to end. The Finale brings an optimistic solution to the tragic parts of the first movement.” Especially effective and haunting are the orchestrations with celesta (think Tchaikovsky’s Nutcracker but hip) and solo violin.

The Fifth Symphony by Shostakovich, comes from 1937, which always surprises me for some reason, I think it sounds more modern than the 1930s. It certainly struck a chord (pun INTENDED) with the Soviets, at its premiere it was well regarded (talk about a time for a standing ovation, all too common today, but for this symphony’s world premiere, I can’t think of a more deserving work!) Shostakovich himself stated: “The idea behind my [Fifth] symphony is the making of a man. I saw him, with all his experience, at the centre of the work, which is lyrical from beginning to end. The Finale brings an optimistic solution to the tragic parts of the first movement.” Especially effective and haunting are the orchestrations with celesta (think Tchaikovsky’s Nutcracker but hip) and solo violin. The Tenth Symphony has quite a history, sketches exist from 1946; it was reportedly finished in 1951 – but Shostakovich maintained in was written in the late summer of 1953. Nevertheless when it was written, it is a deeply moving and autobiographical work – premiered after Stalin’s Death. The opening movement is a work unto itself – very long and bleak. I always imagine Siberia listening to it. The second movement is perhaps my favorite with percussion and is just a movement that flys by…a scherzo, described in Testimony as "a musical portrait of Stalin, roughly speaking". The next movement has two musical themes: D S C H (i.e. Dmitri Shostakovich) and E La Mi Re A (Elmira Nazirova, a student of his, whom he was in love. Pictured above.) Finally in the finale we hear a Georgian hopak, and a return of the DSCH theme.

The Tenth Symphony has quite a history, sketches exist from 1946; it was reportedly finished in 1951 – but Shostakovich maintained in was written in the late summer of 1953. Nevertheless when it was written, it is a deeply moving and autobiographical work – premiered after Stalin’s Death. The opening movement is a work unto itself – very long and bleak. I always imagine Siberia listening to it. The second movement is perhaps my favorite with percussion and is just a movement that flys by…a scherzo, described in Testimony as "a musical portrait of Stalin, roughly speaking". The next movement has two musical themes: D S C H (i.e. Dmitri Shostakovich) and E La Mi Re A (Elmira Nazirova, a student of his, whom he was in love. Pictured above.) Finally in the finale we hear a Georgian hopak, and a return of the DSCH theme.I’ll also include a “dated” piece from the composer himself. Shostakovich made this artistic (read "politcal") statement in the New York Times: “There can be no music without an ideology. The old composers, whether they knew it or not, were upholding a political theory. Most of them, of course, were bolstering the rule of the upper classes. Only Beethoven was a forerunner of the revolutionary movement. If you read his letters, you will see how often he wrote to his friends that he wished to give new ideas to the public and rouse it to revolt against its masters.

On the other hand, Wagner’s biographers show that he began his career as a radical and ended it as a reactionary. His monarchistic patriotism had a bad effect on his mind. Perhaps it is a personal prejudice, but I do not consider Wagner an important composer. It is true that he is played rather frequently in Russia today; but we hear him in the same spirit with which we go to a museum to study forms of the old regime. We can learn certain technical lessons from him, but we do not accept him.

We, as revolutionists, have a different conception of music. Lenin himself said that, “music is a means of unifying broad masses of people.” Not a leader of masses, perhaps, but certainly an organizing force! For music has the power of stirring specific emotions in those who listen to it. No one can deny that Tchaikovsky’s Sixth Symphony produces a feeling of despair, while Beethoven’s Third awakens us to the joy of struggle. Even the symphonic form, which appears more than any other to be divorced from literary elements, can be said to have a bearing on politics. Thus we regard Scriabin as our bitterest musical enemy, because Scriabin’s music tends to an unhealthy eroticism, also to mysticism and passivity, and escape from the realities of life.

Not that the Soviets are always joyous, or supposed to be. But good music lifts and heartens and lightens people for work and effort. It may be tragic but it must be strong. It is no longer an end in itself but a vital weapon to the struggle. Because of this, Soviet music will probably develop along different lines from any the world has known. There must be a change! After all, we have entered a new epoch, and history has proved that every age creates its own language.”

(from an interview with Rose Lee and the New York Times and printed in The Book of Modern Composers by David Ewen, Knopf 1950, pp379-80.)

For more information:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dmitri_Shostakovich

http://w3.rz-berlin.mpg.de/cmp/shostakovich.html

http://www.siue.edu/~aho/musov/dmitri.html

And finally, from Kunst and Kultur:

http://kunku.blogspot.com/2005/12/symphony-shostakovitch-never-wrote.html

The Symphony Shostakovitch Never Wrote

The neatly-gentrified Mtsensk District plaster

buckles in all the right grey-painted places;

the aged, yellowing windows rise and fall

in fashionable decay. A well-upholstered citizen's

slum, drawn to exacting state specifications.

Local housing authorities recommend the childless

to abandon empty ravagings and become a true home.

I found a bare mattress with a soft, sagging middle age

lying in the center of the room. Upon closer examination,

I am pleased to report the womb is uncorrupted

by any illusions of hunger. Smart comrades rent

their own firesides to eat there nightly.

Neither a heart's central heat

nor a bloodstream's warm water

can find domicile with me; I am no icon.

After five doses of vodka prescribed

by my black marketeer, I'm a mere after-dark

sight for our revolution's children.

Aurora's explosions sprawl naked across

the wall, dreamlessly, in bourgeois fever

trying to silence gunship blades echoing

from the Hazarajat right through to my pillows.

The unscreened view overlooks the dingy

proletarian neighbors, unauthorized residents,

and a tinkling factory, where obsolete radio

parts are inefficiently manufactured by badly

motivated workers who over-scent the local Metro.

In the bitter dawn, poverty-stricken May Day

hero workers gather round the closed windows

of our privileged district, marching

to the song of an infant poet, compelling

unsympathetic voices to show solidarity.

Were the pain of that night katyusha,

a great people's victory would be assured.

The unclad working class panorama would slam

rusted doors on the promised land, ransack

determined belief from our official atheism.

I invite a young collectivist neighbor to join mein a meal.

We feed on each other's secret poetry,

drinking the communal smell of our voices

in the candle's scarlet; unaligned, our bodies

soon form their own brethren ministry.

The flat was overheated with the neighbor,

our bodies calling for vodka, the floor our towel.

He leaves in the morning, but occupies my mind

like a liberating people. I evade my soft job

and picnic alone in the Gor'kiy, realizing

the neighboring fantasy is a careless footfall

down a crooked staircase. I know each naked

picture is a counter-revolutionary flight

of relentlessly westward steps no trial

will slow. Somehow my frightened tears remain

hidden until I reach my building and find him

waiting for me in my mailbox. Our bodies

take an exploitive angle under the aristocratic

slump in the wall, covered with the newly-unclassified

pictorial potpourri depicting the State secret

of my love's childhood, from the Masurian Lakes

to the Pripet Marshes. We begin to read hundreds

of official pages, thousands of approved words,

medal-winning chapters of caged images put down

on pages torn from the closed eyes of my young

neighbor, down on the brown Tajik carpeting.

With conspiratorial pride, I lie beside him

and gaze up at the colorful Sputniks looming

over our conversation. I then lie even more,

to the watchers, to the listeners, and to myself,

over and over, lying about love in general, and

this, my unapproved, underground love, in particular.

I feel every inch of our joined bodies being

faithfully documented by Sinyavsky and Daniel;

when my young neighbor finally falls asleep,

I chronicle this obscurantist passion of ours

in a small notebook autographed by hero-poet

Zhenia. The following weekend, we eat unshelled

Cuban peanuts and drink post-colonial African beer.

We do each other's banned homework between

our committee's approved texts. We crash

down aging Tsarist staircases to dissent,

and crash back up with medal-winning heroism.

We rest inside our bedded gulag, a mutual blasphemy

one great, unobeyed ukase, our traitorous lie

as yet unpunished in any Sibirskoye labor camp.

Over morning tea and bread, I muster the courage

to send my unclothed chronicles to another

confidential friend at one of the State

publishing houses. Weeks later, Zhenia himself

mails us a precocious reflection of my young

neighbor and I. We read the dangerously human

verse over and over until our tears overcome us.

With Shostakovich candle-lit in the certainty

of the background, we intrude in each other's body,

spending the Decembrist night in a mutual unlight.

Waking, without the poetry of freedom,

a distressingly human-like tear

fell from my eyes, drowning the sight

of my loved one, a brother poet steeped

in our mutual mother, this holy Russia.

Like a greedy litter, we clamor for her

drooping breasts, warm with the blood

of anonymous masses, sweet with the milk

of our masters, our dirty hands and uneven

teeth pulling, sucking and wailing as we

maneuver for more. Without our sleeping mother,

life is a rocky Baltic crag, a cold memorial

wind-swept with the adolescent mysteries

of a million Petersburg call-boys. I met

one such prostitute, a glorious people's

achievement, along one of the Neva's

crumbling bridges. Our speculative rapture

was realist art, elation enough to arrange

the next debased sunset, a falling curtain

of scarlet irony we and the State could take

enormous pride in. At our bus stop,

the exploding babushkas cast icicles at us

standing among them, naked in the March frost,

dispassionately knowing we so irregular

are but a pogrom away from baby Jesus.

Our continuing humiliated childhood was a village apart,

not on the maps, burned to the ground

in some battle no one remembers; its ashes

burn my feet as I inspect a gravesite,

accompanied by another Komsomol hustler,

who was very thorough in his feigned mourning.

I think my tears made damp white imprints

in the snow, but Komsomol wiped them clean,

and progressed to my heart: "Death is still

far off," he whispered, making me believe him

with committee-scripted words made of kisses,

and the even more terrible policies of his body.

The early illusion of our beautiful slander

took place, down in the Karelian pine needles,

unwatched and unremarked on by the passing animals,

cryptic time, or police surveillance; back

in the city, watching an arrest sidled me with fear.

Returning to my neighborless apartment gave me fatigue.

That night, less the Boyar, I slept alone, in a tomb

of my genetics and the misfortune of my metaphysics.

Like those lads I rent, these sensual stretches

come and go, withdrawn from the front by bumbling

generalship of my warmth; how ashamed one is,

alone in a train station lobby with censored

newspapers and Kazak cigarettes, counting

boys as if they were a marshal's medals,

waiting for sealed traina to make me older

and better versed. I can imagine the fear,

coming to the hero's cemetery to bid adieu

to sullen dreams of the wounded.

Our envious, old friends, Vulcan's cannon-fodder,

twisted needles in the hellish, Teutonic haystack

created whole rivers of spilt blood for our uncle,

promising drink to the parched livestock on the

edge of our Muscovite homeland. I congratulate

the kulaks, who now part with us. In their small,

untroubled villages, they are famous, but outside,

they are the very season of grey

that make the passage of depressing hours

knock trustfulness from my soul, because

my bureau knows, gloomily, they are the next

meal for the terrible steel.

My traitorous westward letter was a lament

for my imprisoned, naked brothers. Like

a reminder of a sobbing infant, stripped

and always in danger, their sweet light

died in the marble hall, under orders,

at once, at first light - unfit, unpatriotic,

and unrequited, my queer brethren die, lying

to the young about youth, lying to the liars

about the lie. I've been reading how such pure

blood falls apart. All of Moscow believed it,

but stayed mute, strange to the demolished

church of our lost Israel, our family's

wandering pastels lost in the gilt edges

of the apostolic icons squirrled away

in the rain-soaked timber of the Dnieper,

for children who might choose to pray

in the post-nuclear future. Despite

the danger, Komsomol kept calling me.

He kept coming to the Ministry, coming

every night in the laughable safety of my arms.

As a bad joke cracked over our last cigarette,

I asked for every one of my roubles back.

Without his usual street-ridden suspicion,

Komsomol produced them from his pants. He

rolled the notes into an exotic surrogate cigarette,

which we smoked after kissing through our laughter.

Komsomol wanted a honeymoon, but insisted it be kept

secret. Night licked the fires in my heart silent

believe me, not every love sprouts love - sometimes,

it just comes, like frozen breath on the train

coach window as the Finnish frontier was passed,

and we made love for the first time,

liberated and admitted into each other.

Komsomol's young, white body was a laid-back shore

that let me sweep over it, wave by wave,

with the dark green and grey depths of my uniform

surging behind, a grim threat to the sand castles

crumbling around the edges near his soul.

For troubled weeks, we rustled beneath the quilts

of a disappeared comrade's dacha bed, like Gogol,

gnawing into the boy until we became one.

The subway was really talking now. The saliva

had frozen on our lips and made them red;

We had put each other's overcoats on,

making a bad match. Our fur hats were neither

stylish nor very impressive; until the Zil

limousine came to fetch us home, back

to Dzerzhinsky Square, the crowd's sniggering

gave off smoke in its derision. Their subsequent

silence made the ensuing poetry of our whispers

more expressive, hiding in the black leather

luxury of the car. Each of our fingers were cold

until we wrapped them up and satisfied the last

side street we hadn't explored. Weeks would pass

until we could make unofficial love again,

on another train, perhaps this time unsealed,

to Prague, to read poetry under the Charles Bridge,

to feed on each other's appetite against the Hunger Wall.

The mere mention of Bohemia reduces Komsomol to a swoon.

Light died in the winter we called ours. Something

dangerous whispered, 'Give thanks for your tears,'

before the daylight fell to pieces. The bellow

of roaring tanks masked the cursed saltwaterf

lowing from our bridegroom eyes, our cross

of solitudes. In no time at all, the country

house was re-assigned to State servants

of better record and higher quality.

Our feeble hearts were reduced to a provisional strike.

The garden's yellow flowers held fast in solidarity,

but official censure soon put that to an end.

All we had left were the kind ringing of the icicles

that were once thrown at us with motherly love,

their delicate, dissident chimes our only friend,

their carillon lulling us to obedient sleep

despite the nonconformity of our frigid bodies.

The twentieth century sun bathed luxuriously

over our garden ice, making the snow glisten

like a collective growing diamonds instead of wheat.

Memories of the city disappeared under the skin

of the eternal ice and into the gentle white night

that walked past our private gulag,

making Komsomol whimper in captive despair.

What a rude sobering the spring is. Bewitched

by solicitous fathers' guiding, their advice

leaking like sewage from a clover field.

Dwarf birches have begun to blossom

through the cracks in our bedroom window.

Komsomol is very quiet these days, cast off from

his fellows in the cosmopolitan train stations.

He still writes a contented poem to me every day,

like Osip, hides it in my lunch for safe-keeping.

Something about our silent, two-comrade Soviet

is brave, yet, we are betrayed. We live, and are alive.

We are completely free, but, even together,

we are without joy in the falling seasons.

from ZIGEUNERTANZE

Copyright (c.) 2005 by Adam Henry Carriere. All Rights Rerserved.

No comments:

Post a Comment